Ссылки [ править ]

- ^ Dörr Эвелин (2008). «Рудольф Лабан: Танцор с кристаллом», Лэнхэм, Мэриленд: Scarecrow Press, стр. 99-101.

- Перейти ↑ Karina, Lillian & Kant, Marion, (2003) (переводчик: Стейнберг, Джонатан). «Танцоры Гитлера: немецкий современный танец и Третий рейх», Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Berghahn Books, стр. Viii.

- ^ Dörr Эвелин (2008). «Рудольф Лабан: Танцор с кристаллом», Лэнхэм, Мэриленд: Scarecrow Press, стр. 1-8.

- ↑ Рудольф Лабан. Архивировано 2 ноября2006 г. в Wayback Machine. Обширная биография из школы Тринити-Лабан, Лондон.

- ^ Мэннинг, Сьюзен. «Переосмысление Лабана» — обзор книги Веры Малетич «Тело-пространство-выражение: развитие движений и танцевальных концепций Рудольфа Лабана». Хроника танцев , Vol. 11, № 2 (1988), стр. 315–320.

- ↑ Рудольф Лабан, «Meister und Werk in der Tanzkunst», Deutsche Tanzzeitschrift, май 1936 г., цитируется в Horst Koegler, «Vom Ausdruckstanz zum ‘Bewegungschor’ des deutschen Volkes: Rudolf von Laban,» in Intellektuellen im Bannism des National ed. Карл Корино (Гамбург: Hoffmann & Campe, 1980), стр. 176.

- ↑ Карина, Лилиан и Кант, Марион, 2003 (переводчик: Стейнберг, Джонатан). «Танцоры Гитлера: немецкий современный танец и Третий рейх», Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Berghahn Books, стр. 244.

- ↑ Карина, Лилиан и Кант, Марион, 2003 (переводчик: Стейнберг, Джонатан). «Танцоры Гитлера: немецкий современный танец и Третий рейх», Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Berghahn Books, стр. 254.

- ↑ Карина, Лилиан и Кант, Марион, 2003 (переводчик: Стейнберг, Джонатан). «Танцоры Гитлера: немецкий современный танец и Третий рейх», Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Berghahn Books, стр. 256.

- ↑ Карина, Лилиан и Кант, Марион (переводчик: Стейнберг, Джонатан). «Танцоры Гитлера: немецкий современный танец и Третий рейх», Нью-Йорк и Оксфорд: Berghahn Books, 2003.

- ^ Престон-Данлоп, Валери. «Рудольф Лаван: необычная жизнь» (Dance Books, 1998) (особенно глава 9 «Нацификация культуры» и глава 10 «Выживание»).

- ^ Кью, Кэрол. «От хора Веймарского движения до танцев нацистской общины: взлет и падение« Фесткультуры »Рудольфа Лавана». Танцевальные исследования: Журнал Общества танцевальных исследований , Vol. 17, No. 2 (1999): pp. 73–96.

England

He was allowed to travel to Paris in 1937 and from there he went to England. He joined the Jooss-Leeder Dance School at Dartington Hall in the county of Devon where innovative dance was already being taught by other refugees from Germany.

He was greatly assisted in his dance teaching during these years by his close associate and long-term partner Lisa Ullmann. Their collaboration led to the founding of the Laban Art of Movement Guild (now known as The Laban Guild for Movement and Dance) in 1945 and the Art of Movement Studio in Manchester in 1946. Laban was a friend of Carl Jung and Josef Pilates (inventor of the Pilates method of physical fitness).

In 1947, he published a book Effort, Fordistic study of the time taken to perform tasks in the workplace and the energy used. He tried to provide methods intended to help workers to eliminate «shadow movements» (which he believed wasted energy and time) and to focus instead on constructive movements necessary to the job in hand. He published Modern Educational Dance in 1948 when his ideas on dance for all including children were taught in many British schools.

He died in the UK.

Among Laban’s students, friends, and associates were Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss, Lisa Ullmann, Albrecht Knust, Lilian Harmel, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Hilde Holger, Gertrud Kraus, Gisa Geert, Warren Lamb, Elizabeth Sneddon, and Yat Malmgren.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dörr, Evelyn. Rudolf Laban: The Dancer of the Vrystal. Scarecrow Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0810860070

- Hodgson, John. Mastering Movement: The Life and Work of Rudolf Laban. Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0878300805

- Karina, Lilian, and Marion Kant. Hitler’s Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich. New York: Berghahn Books, 2003. ISBN 1571813268

- Kew, Carole. «From Weimar Movement Choir to Nazi Community Dance: The Rise and Fall of Rudolf Laban’s ‘Festkultur’.» Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research 17(2) (1999).

- Von Laban, Rudolf. Laban’s Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. Plays, inc., 1975. ISBN 082380187X

- Von Laban, Rudolf, and Lisa Ullman. The Mastery of Movement. Plays, Inc., 1971. ISBN 0823801233

- Von Laban, Rudolf, and F.C. Lawrence. Effort: Economy in Body Movement. Plays, inc. 1974. ISBN 0823801608

Veröffentlichungen

- Autor

- Die Welt des Tänzers. Seifert, Stuttgart 1920.

- Gymnastik und Tanz. Stalling, Oldenburg i.O. 1926.

- Choreographie. Erstes Heft von fünf geplanten Heften. Diederichs, Jena 1926.

- Des Kindes Gymnastik und Tanz. Stalling, Oldenburg i.O. 1926.

- Ein Leben für den Tanz. Erinnerungen. Dresden 1935

- Die tänzerische Situation unserer Zeit. Ein Querschnitt. Dresden 1936

- Der moderne Ausdruckstanz in der Erziehung. Eine Einführung in die kreativ tänzerische Bewegung als Mittel zur Entfaltung der Persönlichkeit. Gemeinsam mit Lisa Ullmann. Heinrichshofen, Wilhelmshaven 1984.

- Principles of dance and movement notation. (dt. Kinetografie — Labanotation. Einführung in die Grundbegriffe der Bewegungs- und Tanzschrift. Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1995. ISBN 3-7959-0606-7)

- Choreutics. (dt. Choreutik. Grundlagen der Raumharmonielehre des Tanzes. Noetzel, Wilhelmshaven 1991. ISBN 3-7959-0581-8)

- Herausgeber

Deutsche Tanzfestspiele 1934 unter Förderung der Reichskulturkammer. Reißner, Dresden 1934. (Enthält Beiträge u.a. von Hans Brandenburg, Yvonne Georgi, Dorothee Günther, Harald Kreutzberg, Gret Palucca und Mary Wigman.)

биография

Резу Лабан родился в 1879 году в семье австро-венгерского военного, французского происхождения, и матери английского происхождения. Он занимается традиционным венгерским танцем ( csárdás ), затем с 1907 года изучает искусство в Школе изящных искусств в Париже . Его интересует связь человеческого движения с пространством, которое его окружает. Он сосредоточился на искусстве движения ( Bewegungskunst ) и выразительном танце ( Ausdruckstanz ) и в этом духе основал школу в Мюнхене в 1910 году, ученицей которой была Мэри Вигман .

Во время Первой мировой войны он создал в Швейцарии, в Асконе, на Монте Верита, школу, которая вскоре присоединилась ко многим сторонникам современного танца. Здесь он читал летние курсы (1913-1919). В 1917 году в Монте-Верита прошел «Национальный конгресс Ordo Templi Orientis», на котором пытались объединить теософов, вегетарианцев, оккультистов и пацифистов с целью остановить продолжающуюся войну. В этом контексте Лабан предлагает «Праздник Солей», который проходит от заката до рассвета 18 и19 августа. Он встретил музыканта Эмиля Жак-Далькроза, за которым последовал в Дрезден, вернувшись в Германию в 1919 году. В 1923 году он основал свой собственный театр в Гамбурге, посвященный танцам ( Tanzbühne Laban ), а в 1927 году — Институт хореографии из Берлина .

В 1928 году он опубликовал « Кинетографию Лабан», в которой предложил систему обозначений для основных танцевальных движений, впоследствии названную лабанотацией . Эта система теперь используется не только в хореографии, но и в других областях, например, в культурных произведениях, невербальном общении и т. Д.). Она также предлагает танцевальные движения для масс, то есть искусство «движущегося хора».

С 1930 по 1934 год он дирижировал балетом Берлинской оперы, а затем несколькими танцевальными фестивалями при поддержке министра пропаганды Йозефа Геббельса . Без реального политического участия Лаван следует идеологии национал-социализма, дискриминируя, в частности, неарийцев. В Берлине он организовал «хореографию» спортсменов во время летних Олимпийских игр 1936 года .

Однако от Джозефа Геббельса отрекся, он пользуется преимуществом пребывания в Париже в 1937 году, чтобы добраться до Англии и поселиться в Дартингтон-холле (штат Нью-Йорк ) . Там он разработал систему анализа движений, благодаря изучению рабочих на работе и пациентов с психомоторными расстройствами. Он основал Гильдию Искусства Движения Лабана в 1945 году и Студию Искусства Движения в Манчестере в 1946 году.

Leben

Rudolf von Laban – Sohn eines hochrangigen österreichisch-ungarischen Militär – war zunächst Csárdástänzer. Seit 1907 studierte er Kunst in Paris. 1910 gründete Laban in München seine erste Tanzgruppe. Während des Ersten Weltkrieges schuf er auf dem Monte Verità im schweizerischen Ascona eine Schule, die bald viele Anhänger der neuen Tanzkunst anzog. Hier führte Laban von 1913 bis 1919 seine berühmten Sommerkurse für Tanz durch; und kam mit Emile Jaques-Dalcroze in Kontakt, dem er nach Hellerau bei Dresden folgte.

Den Abschluss eines großen vegetarischen und pazifistischen Kongresses Ende Sommer 1917 bildete das dreiteilige Tanzdrama „Sang an die Sonne“ nach einem Text von Otto Borngräber. Es begann mit dem Untergang der Sonne, worauf der Tanz der Dämonen der Nacht folgte. Frühmorgens wurde die aufgehende, „siegende“ Sonne begrüßt als Ausdruck für die Hoffnung der Überwindung des Krieges und einer utopischen Höherentwicklung der Menschheit.

Tanzunterricht im Choreographischen Institut Laban Berlin 1929

Im Jahr 1922 gründete Laban in Hamburg die Tanzbühne Laban. 1923 folgte die Gründung der ersten Laban-Schule, dem ein eigener Bewegungschor angeschlossen war. Die zahlreichen Absolventen der Hamburger Schule trugen Labans Methode erfolgreich in verschiedene Städte in Deutschland und Europa weiter. In den Folgejahren entstanden auf diese Weise europaweit 24 Laban-Schulen.

Darüber hinaus baute Laban in Würzburg (1926/27) und Berlin (1928/29) ein Choreographisches Institut auf. Gemeinsam mit Dussia Bereska leitete er außerdem die Kammertanzbühne (1925-27). Von 1930 bis 1934 übernahm er die Leitung des Balletts der Deutschen Staatsoper (Lindenoper) in Berlin. Eine sehr enge Zusammenarbeit verband ihn mit Joseph Hubert Pilates, einem Visionär der Bewegung und des Körpers.

Nachdem er 1936 noch die Choreographie der Olympischen Sommerspiele vorbereitet hatte, flüchtete er 1937 vor den Nationalsozialisten nach Manchester. In der Nähe von London gründete Laban mit Unterstützung des englischen Unterrichtsministeriums ein Bewegungsstudio, in dem er bis zu seinem Tode tätig war.

Im Jahr 1966 wurde in Wien Döbling (19. Bezirk) der Labanweg nach ihm benannt.

Внешние ссылки [ править ]

| Викискладе есть медиафайлы по теме Рудольфа фон Лабана . |

- Путеводитель по Икосаэдру Рудольфа Лабана. Специальные коллекции и архивы, Библиотеки Калифорнийского университета в Ирвине, Ирвин, Калифорния

- Рудольф Лабан — биография с сайта Тринити Лабан

- Лимсонлайн Лабан / Институт исследований движения Бартениефф — LIMS NYC

- Краткие биографии Лавана и некоторых ведущих практиков Лавана — сайт проекта Лабан

- EUROLAB — Европейская ассоциация исследований движения Лабана / Бартениева

- Сертификационные программы EUROLAB в исследованиях движения Лабана / Бартениева

- Бесплатные партитуры Рудольфа фон Лабана в рамках Международного проекта библиотеки музыкальных партитур (IMSLP)

| Авторитетный контроль |

|

|---|

Share and Cite

MDPI and ACS Style

Brandl, F.L. On a Curious Chance Resemblance: Rudolf von Laban’s Kinetography and the Geometric Abstractions of Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Arts 2020, 9, 15.

https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010015

AMA Style

Brandl FL. On a Curious Chance Resemblance: Rudolf von Laban’s Kinetography and the Geometric Abstractions of Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Arts. 2020; 9(1):15.

https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010015

Chicago/Turabian Style

Brandl, Flora L. 2020. «On a Curious Chance Resemblance: Rudolf von Laban’s Kinetography and the Geometric Abstractions of Sophie Taeuber-Arp» Arts 9, no. 1: 15.

https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010015

Find Other Styles

Note that from the first issue of 2016, MDPI journals use article numbers instead of page numbers. See further details here.

6. Conclusions

Given the arguments presented in this paper, we may conclude that Sophie Taeuber-Arp occupies a unique role in the complex relationships between the Dada movement and the work of Rudolf von Laban. While aspects of Taeuber-Arp’s oeuvre are certainly influenced by her involvement in the circles of Zurich Dada, her pedagogical writings about the applied arts resonate much more strongly with the theoretical investments of Rudolf von Laban. Both emphasize dedication and practice over chance creation, individual virtuosity over anonymity, and precision over chaos. It is these pedagogical and conceptual concordances that finally make clear why the resemblances between Taeuber-Arp’s and Laban’s visual languages are not a matter of pure coincidence.

Putting this main conclusion in a larger context, this sheds new light on the manifold interactions between Dada and expressionist dance, asking us to revise our assumptions about their supposedly distinct artistic agendas. Most importantly, however, this paper hopes to have added insights to early geometric abstraction’s intimate ties not only to the applied arts, but also to the dancing body. This is only one possible way in which to reconsider the role of the corporeal in the history of modernism.

Life and work

Rudolf von Laban was born in Pozsony (now Bratislava) in 1879 in the Kingdom of Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire, into an aristocratic family. His father’s family had come from the French nobility (De La Banne, from a French crusader stranded in Kingdom of Hungary in the 13th century) and Hungarian nobility, and his mother’s family was from France. His father was a field marshal of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the governor of the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He spent his childhood in the courtly circles of Vienna and Bratislava, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the towns of Sarajevo and Mostar.

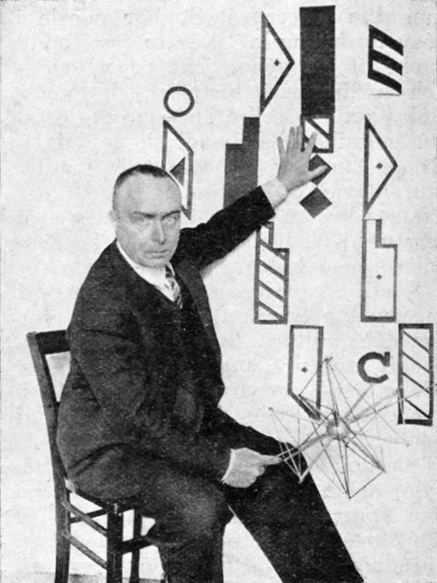

Enrolled by his father as a cadet in the Military Academy at Wiener Neustadt, he left to study architecture at the Écoles des Beaux Arts in Paris. During his stay in Paris, Laban became interested in the relationship between the moving human form and the space which surrounds it. He then moved to Munich at age 30 and under the influence of seminal dancer/choreographer Heidi Dzinkowska began to concentrate on Bewegungskunst, more commonly called Ausdruckstanz, or the movement arts spending the summer months of 1913 and 14 directing the school for the Arts at the alternative community at Monte Verita, Switzerland.

He established choreographic training centres in Zürich in 1915, and later set up branches in Italy, France, and central Europe.

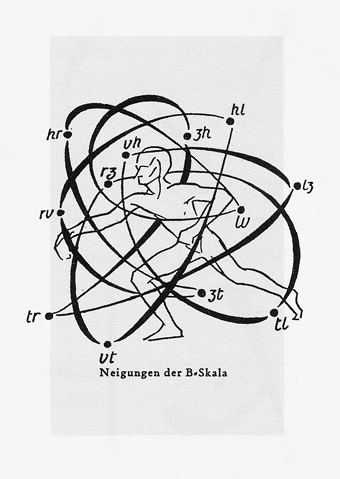

One of his great contributions to dance was his 1928 publication of Kinetographie Laban, a dance notation system that came to be called Labanotation and is still used as one of the primary movement notation systems in dance. His theories of choreography and movement are now foundations of modern dance and dance notation (choreology). Later they were applied in other fields, including cultural studies, leadership development, and non-verbal communication theory.

Laban developed the art of movement choir, wherein large numbers of people move together in some choreographed manner, but that can include personal expression. This aspect of his work was closely related to his personal spiritual beliefs, based on a combination of Victorian theosophy, Sufism, and popular fin de siecle Hermeticism. By 1914 he had joined the Ordo Templi Orientis and attended their ‘non-national’ conference in Monte Verità, Ascona in 1917, where he directed ^The Song to the Sun^ performed on the Ticino hillside. Laban had founded a summer dance program in Ascona in 1912, which continued until 1914, when World War I broke out.

1. Introduction

This essay lingers on the apparent contingency of what appears to be a striking visual resemblance: that between a modern system of dance notation and early modernist abstract art. To do so, it brings together the lives and works of the choreographer and dance theoretician Rudolf von Laban with those of the artist and pedagogue Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Today, Laban’s name is famous not only for his contributions to German expressionist dance, but also for his invention of Kinetography, a system for the recording of dance using abstract symbols, which he developed in the first decades of the 20th century. Known today as Labanotation, it continues to be amongst the prevalent systems of movement notation and analysis. During the early stages of its development, Laban frequented similar artistic circles as Sophie Taeuber-Arp, who at the time was developing her abstract visual language in textile design and other media of the applied arts. Jill Fell is not alone in having drawn attention to a potential artistic conversation between these two artists, but up to now no thorough research into the nature of this connection between Rudolf von Laban and Sophie Taeuber-Arp has been undertaken.

Germany

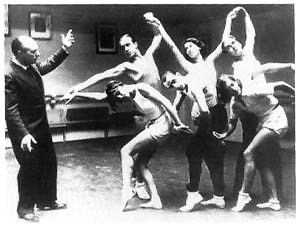

Between 1921 and 1929 he directed the Tanzbühne Laban and smaller group Kammertanzbühne Laban creating and touring dance theatre works and devising movement choirs for amateur dancers. He initiated three Dance Congresses in 1927, 1928 and 1930 to further the role of dance and the status of the dancer in Germany.

From 1930 to 1934 he was director of the Allied State Theatres in Berlin, Germany. In 1934, he was promoted to director of the Deutsche Tanzbühne, in Nazi Germany.

He directed major festivals of dance under the funding of Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry from 1934-1936. Laban even wrote during this time that «we want to dedicate our means of expression and the articulation of our power to the service of the great tasks of our Volk. With unswerving clarity our Führer points the way». In 1936 Laban become the chairman of the association «German workshops for dance» and received a salary of 1250RM per month, but a duodenal ulcer in August of that year bed bound him for two months, eventually leading him to ask to reduce his responsibilities to consultancy. This was accepted and his wage reduced to 500RM, his employment then ran until March 1937 when his contract ended. Several allegations of Laban’s attachment to Nazi ideology have been made, for instance that as early as July 1933 he was removing all pupils branded as non-Aryans from the children’s course he was running as a ballet director. However, some Laban scholars have pointed out that such words and actions were necessary for survival in Germany at that time, and that his position was precarious as he was neither a German citizen nor a Nazi party member. His work under the Nazi regime culminated in 1936 with Goebbel’s banning of Vom Tauwind und der Neuen Freude (Of the Spring Wind and the New Joy) for not furthering the Nazi agenda.

Legacy

Laban’s theories of choreography and movement served as one of the central foundations of modern European dance. Today, Laban’s theories are applied in diverse fields, such as cultural studies, leadership development, non-verbal communication, and others.

In addition to the work on the analysis of movement and his dance experimentations, he was also a proponent of dance for the masses. Toward this end, Laban developed the art of the movement choir, wherein large numbers of people move together in some choreographed manner, which includes personal expression.

This aspect of his work was closely related to his personal spiritual beliefs, based on a combination of Victorian Theosophy, Sufism, and popular Hermeticism.

By 1914, he had joined the Ordo Templi Orientis and attended their ‘non-national’ conference in Monte Verita, Ascona in 1917, where he also set up workshops popularizing his ideas.

Currently, major dance training courses offer Laban work in their curricula. However, Laban maintained that he had no «method» and had no wish to be presented as having one. His notation system, however, is still the primary movement notation system in dance.

Literatur

- Ingeborg Baier-Fraenger: Der Aufbau der Kinetographie Laban. In: Christof Baier (Hrsg.): Das Erbe Wilhelm Fraengers. Erinnerungen an Ingeborg Baier-Fraenger (1926-1994). Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, Potsdam 2009, S. 201−208 ISBN 978-3-86650-036-5

- Fritz Böhme: Rudolf von Laban und die Entstehung des Modernen Tanzdramas. Edition Hentrich, Berlin 1996 ISBN 3-89468-217-5

- Evelyn Doerr: Rudolf Laban — The Dancer of the Crystal. Scarecrow Press 2009, Lanham, Maryland, Toronto, Plymouth, UK. ISBN 978-0-8108-6007-0

- Evelyn Doerr: Rudolf Laban — Die Schrift des Tänzers. Ein Portrait. Norderstedt 2005 ISBN 3-8334-2560-1

- Evelyn Doerr: Rudolf Laban — Das choreographische Theater. Die erste vollständige Ausgabe des Labanschen Werkes. Norderstedt 2004 ISBN 3-8334-1606-8

- John Foster: The influence of Rudolph von Laban. Lepus Books, London 1974, 1977 ISBN 0-86019-015-3

- Valerie Preston-Dunlop: Rudolf Laban – An Extraordinary Life. Dance Books, London 1998 ISBN 1-85273-060-9

- Mary Wigman: Rudolph von Laban zum 50. Geburtstag. In: Schrifttanz. Hrsg. von der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Schrifttanz. Universal-Ed., Wien 4.1929, 65; Olms, Hildesheim 1991 (in einem Bd.) ISBN 3-487-09537-8

Works and publications

(Undated). Harmonie Lehre Der Bewegung (German). (Handwritten copy by Sylvia Bodmer of a book by Rudolf Laban) London: Laban Collection S. B. 48.

(1920). Die Welt des Taenzers (German). Stuttgart: Walter Seifert. (3rd edition, 1926)

(1926). Choreographie: Erstes Heft (German). Jena: Eugen Diederichs.

(1926). Gymnastik und Tanz (German). Oldenburg: Stalling.

(1926). Des Kindes Gymnastik und Tanz (German). Oldenburg: Stalling.

(1928). Schriftanz: Methodik, Orthographie, Erlaeuterungen (German). Vienna: Universal Edition.

(1929). «Das Choreographische Institut Laban» in Monographien der Ausbildungen fuer Tanz und Taenzerische Koeperbildung (German). Edited by Liesel Freund. Berlin-Charlottenburg: L. Alterthum.

(1947). with F. C. Lawrence. Effort: Economy of Human Movement London: MacDonald and Evans. (4th reprint 1967)

(1948). Modern Educational Dance. London: MacDonald and Evans. (2nd Edition 1963, revised by Lisa Ullmann)

(1948). «President’s address at the annual general meeting of the Laban art of movement guild». Laban Art of Movement Guild News Sheet. 1 (April): 5-8.

(1950). The Mastery of Movement on the Stage. London: MacDonald and Evans.

(1951). «What has led you to study movement? Answered by R. Laban». Laban Art of Movement Guild News Sheet. 7 (Sept.): 8-11.

(1952). «The art of movement in the school». Laban Art of Movement Guild News Sheet. 8 (March): 10-16.

(1956). Laban’s Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. London: MacDonald and Evans. (2nd edition 1975, annotated and edited by Roderyk Lange)

(1960). The Mastery of Movement. (2nd Edition of The Mastery of Movement on the Stage), revised and enlarged by Lisa Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans. (3rd Edition, 1971. London: MacDonald and Evans) (1st American Edition, 1971. Boston: Plays) (4th Edition, 1980. Plymouth, UK: Northcote House)

(1966). Choreutics. Annotated and edited by Lisa Ullmann. London: MacDonald and Evans.

(1974). The Language of Movement; A Guide Book to Choreutics. Annotated and edited by Lisa Ullmann. Boston: Plays. (American publication of Choreutics)

(1975). A Life For Dance; Reminiscencs. Translated and annotated by Lisa Ullmann. London: MacDonald & Evans. (Original German published 1935.)

Life and work

Rudolf von Laban was born in Pozsony (now Bratislava) in 1879 in the Kingdom of Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Empire, into an aristocratic family. His father’s family had come from the French nobility (De La Banne, from a French crusader stranded in Kingdom of Hungary in the 13th century) and Hungarian nobility, and his mother’s family was from England. His father was a field marshal of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the governor of the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He spent his childhood in the courtly circles of Vienna and Bratislava, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the towns of Sarajevo and Mostar.

Laban initially studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

During his stay in Paris, Laban became interested in the relationship between the moving human form and the space which surrounds it. He then moved to Munich at age 30 and under the influence of seminal dancer/choreographer Heidi Dzinkowska began to concentrate on Bewegungskunst, more commonly called Ausdruckstanz, or the movement arts.

In Zürich in 1915, Laban established the Choreographic Institute with branches later founded in Italy, France, and central Europe.

One of his great contribution to dance was his 1928 publication of Kinetographie Laban, a dance notation system that came to be called Labanotation and is still used as one of the primary movement notation systems in dance. His theories of choreography and movement are now foundations of the modern dance. Later they were applied in Cultural Studies, Leadership development, Non-Verbal Communication, and other fields.

Laban developed the art of movement choir, wherein large numbers of people move together in some choreographed manner, but that can include personal expression. This aspect of his work was closely related to his personal spiritual beliefs, based on a combination of Victorian Theosophy, Sufism, and popular fin de siecle Hermeticism. By 1914 he had joined the Ordo Templi Orientis and attended their ‘non-national’ conference in Monte Verità, Ascona in 1917, where he also set up workshops popularizing his ideas.

Laban had founded a summer dance program in Ascona in 1912, which continued until 1914, when World War I broke out.

From 1930 to 1934 he was director of the Allied State Theatres in Berlin, Germany. In 1934, he was promoted to director of the Deutsche Tanzbühne, in Nazi Germany.* -extensive biography from Trinity-Laban School, London

He directed major festivals of dance under the funding of Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry from 1934-1936.Manning, Susan. «Reinterpreting Laban» a review of «Body-Space-Expression: The Development of Rudolf Laban’s Movement and Dance Concepts» by Vera Maletic. Dance Chronicle, Vol. 11, No. 2 (1988), pp 315-320 Laban even wrote during this time that «we want to dedicate our means of expression and the articulation of our power to the service of the great tasks of our Volk. With unswerving clarity our Führer points the way».Rudolf Laban, «Meister und Werk in der Tanzkunst,» Deutsche Tanzzeitschrift, May 1936, quoted in Horst Koegler, «Vom Ausdruckstanz zum ‘Bewegungschor’ des deutschen Volkes: Rudolf von Laban,» in Intellektuellen im Bann des National Sozialismus, ed. Karl Corino (Hamburg: Hoffmann & Campe, 1980), p. 176. Several similar allegations of Laban’s attachment to Nazi ideology have been made, for instance that as early as July 1933 he was removing all non-Aryan pupils from the children’s course he was running as a ballet director.Karina, Lillian & Kant, Marion (Translator: Steinberg, Jonathan). «Hitler’s Dancers: German Modern Dance and the Third Reich» (New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2003) However, some Laban scholars have pointed outPreston-Dunlop, Valerie. «Rudolf Laban An Extraordinary Life» (Dance Books 1998) (especially Chap 9 ‘The Nazification of Culture’ and Chap 10′ ‘Survival’. that such words and actions were necessary for survival in Germany at that time, and that his position was precarious as he was neither a German citizen nor a Nazi party member. His work under the Nazi regime culminated in 1936 with Goebbel’s banning of Vom Tauwind und der Neuen Freude (Of the Spring Wind and the New Joy) for not furthering the Nazi agenda.Kew, Carole. «From Weimar Movement Choir to Nazi Community Dance: The Rise and Fall of Rudolf Laban’s «Festkultur»».Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, Vol. 17, No2 (1999): pages 73-96

← previous next →

Pages: 1 last

![Рудольф фон лабансодержание а также жизнь и работа [ править ]](http://gitara-vrn.ru/wp-content/uploads/7/e/b/7eb0d8461611346f1153f0dcdf47893a.jpeg)